Insight 5-2 | January 3, 2025

Women, Peace and Security Applications in the CAF

Sonal Gupta is an Infantry Reservist at the Princess of Wales’ Own Regiment and a student at Queen’s University, both based in Kingston, Ontario. Sonal is studying Life Sciences and would like to pursue a career with the Canadian Forces Health Services Group. As a born and raised Kingstonian, she has volunteered extensively with meal programs in her community and has amalgamated her culinary and science background into a food literacy not-for-profit for youth at-risk. Through humanitarian service, Sonal is committed to building a healthier and safer future that allows more people to prosper and experience peace in their everyday life.

Time to Read: 10 minutes

Home / Publications / Insights / Insight 5-2

*This article also appears as a chapter in the 2023 KCIS Conference volume that was published Nov. 2024

Background

The past few decades of armed conflict have seen a growing number of civilian casualties. Ongoing geopolitical tension reflects systemic inequalities and disproportional loss in Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) communities. The effects of climate change and extreme weather are now felt universally but continue to displace the most vulnerable. Technology, when created to inflict harm, has unintended consequences for population health and global security. Mismanagement of resources and self-serving governments deny people their basic rights and increase the likelihood of insurgent activity. To address these challenges, international security measures have concentrated on the Protection of Civilians (PoC) to safeguard the population from rapid planetary changes and uncontrolled humanitarian crises.

The United Nations (UN) Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) human security framework overlap on the PoC and collectively oversee the rehabilitation of men, women, and children affected by war.[1] The WPS philosophy is based on the meaningful participation of women at all levels of policymaking and peacebuilding while human security missions reinforces critical infrastructure and provide people in crisis with a sense of stability. Where WPS and human security differ is on the use of weapons, which separates a peace-oriented approach from uniquely military response to conflict.

Soldiers in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) are taught to embrace the “warrior spirit” and uphold the highest standard of service as directed by the Geneva Convention and rules-based international order. This comes with the responsibility of carrying lethal weapons and exercising controlled violence to protect civilians on the ground. Military training combines structure and discipline with a dynamic, experiential style of learning to psychologically prepare soldiers for lawful combat that causes the least amount of collateral damage. In the CAF, the emerging concept of human security has been integrated into both protection and prevention forms of military service which combine sophisticated armed operations with cooperative efforts to preserve human life.[2]

WPS invites an alternative perspective on conflict management through a demilitarised, gender-progressive lens and is next in the human security continuum. The purpose of this report is to demonstrate how WPS principles apply in the combat arms and forecast the most humane outcomes in global peace and security provisions. From the perspective of an infantry soldier, proficiency in the armed forces calls for a delicate balance between skill and sensitivity, and finely tuned intuition for danger to properly navigate the broader cultural context of countries in conflict.

Women, Peace and Security (WPS)

The WPS Research Network prepared 8 eight Key Recommendations for the Canadian government to observe a broader vision of peace (Table 4.1).[3] The WPS vision expands on the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which set the improved status of women and girls and the reduction of military spending, as top priorities for conflict prevention. To meet national objectives for WPS, Canada’s foreign policy will have to re-allocate a portion of the defence budget to disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration programs. This includes ratifying treaties on anti-armament, limiting international arms transfer, and reinvesting in peace and grassroots-led research and development.[4] WPS also recognizes the distinct forms of oppression against women and girls in humanitarian settings and aims to increase access to reproductive health services and offer recourse for conflict related sexual violence (CRSV).[5]

Table 4.1

WPS-RN Key Recommendations for Peace

Demilitarization across all policy areas.

Use “feminism” and feminist principles with integrity.

Reinvest in feminist strategies (diplomacy, conflict prevention) as a core objective of Canadian foreign policy.

Prioritize intersectionality and inclusion in WPS strategies, utilizing diverse participants, representatives, and consultants to shape future initiatives.

Fund institutions and policies that will actively promote peace.

Limit military spending, procurement, and international arms transfers; work towards defunding militarized institutions.

Fulfill existing international commitments for global peace, including ratifying policies to address arms control and disarmament.

Address WPS in domestic contexts, including in practices for addressing sexual violence in military and police institutions, and the role that government and military institutions play in perpetuating ongoing Missing Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) and colonial violence.

In conflict settings, gender-based violence leads to pronounced instability for women and girls and denies them the right to education and decent employment in the formal economy. Dr. Bartels reported on the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti and studied the intersections between gender and CRSV in Haitian society. As a means of alleviating extreme poverty, families sometimes forced women and girls to exchange sex for food, money, and medicine. When UN peacekeepers also partook in transactional sex with locals, it raised concerns about male-dominated forces increasing the potential for CRSV in regions already under siege.[6] Over the last 30 years, more instances of peacekeeper-perpetrated sexual exploitation and abuse have surfaced and disgraced peacekeeping missions almost entirely.[7] The WPS agenda places opportunities for women and girls to attend school and generate income as defining characteristics for lasting peace.

With improved security and socioeconomic status, women in post-conflict states are more inclined to increase participation in domestic assistance programs and invest in social wellness services for food security, education, water sanitation, and rural growth. Wangari Maathai, founder of the Green Belt Movement, addressed famine in eastern Africa by teaching women how to collect water and grow their own food. Her leadership inspired women to capitalise on resources available in the environment, which strengthened the communities’ collective ability to thrive.[8] The empowerment of women and girls in the Global South is at the heart of the WPS agenda and solutions for peace that go beyond intersecting parties and sustain everyone in the long run.

View from the Ranks

Women in the CAF serve across all trades and maintain a core set of credentials to protect people's people’s safety. In some locations, women can access spaces that are restricted to their male counterparts. Under this pretext, NATO forces have deployed female engagement teams to gather information on gender-based inequalities in countries where women’s right have been severely violated.[9] To meet the specific needs of women and girls in conflict, Canada's Canada’s Ambassador for WPS recommends a thorough integration of WPS norms into all areas of CAF policy and practice, for individual soldiers to deliver on de-escalation, restoration, and prevention tactics.[10]

Outside of pre-deployment training and career enrichment opportunities, Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) is the official Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion training guide for soldiers in the CAF. GBA+ is a population assessment tool to provide accessible, gender-informed programming in government-led initiatives. It is mandatory for members of the CAF to complete GBA+ training, ; however, the virtual method of delivery and administrative practice scenarios do not align with the theatre of operation or style of decision-making soldiers encounter when preparing for combat. The profession of arms requires extensive training to override a physiological response to fear and be of sound mind to act in accordance with the law of armed conflict. Consider the following:

A group of armed Canadian soldiers mounted atop a patrol vehicle in Iraq were approached by a burqa-clad woman, who appeared frightened and seemed to be holding something in her arms. Given the language barrier, the woman tried to ask for help by extending her arms and revealing a dead, mutilated baby under her veil. However, the combination of gender, religion, and body-language, fit the stereotype of a suicide bomber, and triggered an immediate “prepare to engage” reaction from the soldier on board.[11]

This story captures the grave implications of unconscious bias when identifying potential combatants. Enemy profiling is an isolated military task that requires careful observation and the ability to determine, in a split second, whether to pull the trigger or not. Canada’s strategic planner for the War in Ukraine, Brigadier General Errington, highlighted the severity of this challenge which inadvertently places more value on white able-bodies and has resulted in more BIPOC casualties in past and current conflicts. GBA+ is a starting point in the reconciliation process to limit the effects of colonial injustices deeply embedded in the CAF. However foreign military intervention is responsible for an existing trust deficit between Western nations and countries in the Global South who did not experience peace over the last 50 years. To bridge these divisions, soldiers in the CAF should receive WPS training on harm mitigation strategies and best practices for PoC.

WPS in the Field

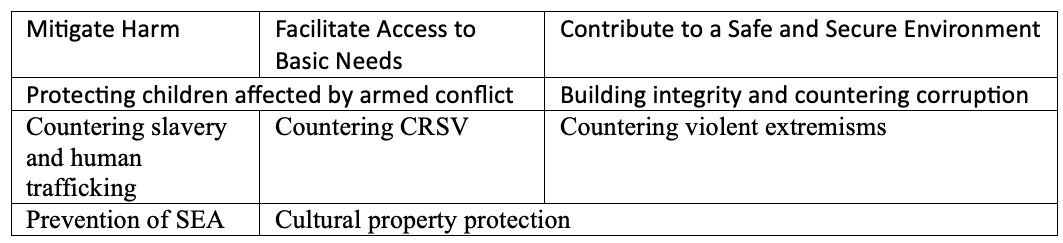

The NATO model for the PoC is based on the first dimension of human security which oversees direct threats to safety, health, and physical integrity (Table 4.2).[12] Traditional stability operations are a top-down form of intervention that follow counter-insurgency protocol to neutralise threats. Current doctrine is evolving towards human security and adopting bottom-up prevention strategies to address the growing number of civilian casualties in the new era of war.[13] This transition from a protection-based to development-based approach is reflected in the recount below:

Captain Gibson from the Peace Support Training Center led me and a group of 10 other soldiers from the Princess of Wales Own Regiment through a stability operations training exercise in Fall 2022. On route, the section lead, who had some familiarity with counter-insurgency protocol, assigned each member of the group a force protection or engagement role. On the outskirts, the section started receiving details of the hostile environment and arrived on site armed and dressed for combat. Those chosen for security were posted on opposite ends of a lookout tower, and the remainder proceeded to enter a mock village district. As the designated scribe, I recorded events as they unfolded and took note of the character’s requests to improve their living conditions.

The first phase of the scenario featured a child soldier who recently returned from boot camp with a local insurgent force. Now comfortable using a weapon, the child began terrorising the compound with a loaded AK-47. A group of 4 soldiers were instructed to locate the child by sweeping through the surrounding dwellings. The child was met by the soldiers at gunpoint. The scene ended after the child started firing bullets into the air and the team of soldiers could do little to intervene.

The second phase introduced media coverage. The section lead was approached in the courtyard by a local journalist who was curious about the role of CAF soldiers in the area. Questions such as “How are you going to clear the landmines off the farms?” and “Can you get these people food and water?” were asked. In this moment, honest and diplomatic responses such as “we will pass your concerns up the chain of command” or “we will follow up with more information” were an effective communication strategy. The reporter was satisfied with the section commander’s assessment, but the scene ended abruptly with the sound of a gunshot.

The third phase took place outside the village quarters. The security team failed to alert those inside that a local girl had been kidnapped by one of the militias in town. By the time we reacted, an unmarked vehicle pulled up in front of the entrance and tossed the girl’s corpse onto the road. There was pin drop silence when the scene closed, and most trainees were in a state of shock.

In our after-action review, Captain Gibson discussed what we could have done differently. Our first mistake was entering a civilian domain with loaded rifles, which was counterproductive to the stability mission. Instead, a line of defence could be formed around the perimeter to send in a detachment of soldiers with weapons slung on their back. Secondly, barging into people’s homes without permission evokes fear and animosity. Instead, meet with the village elder to ask for a guided tour and determine what the deficiencies are. Thirdly, proceeding without establishing contact with the security team does not allow for a timely response to threats. Communication is of the utmost importance.[14]

This station was an opportunity for soldiers to apply the fundamentals of stability operations and gain an appreciation for the lived experiences of people in conflict. Understanding the socioeconomic and cultural nuances of the operating environment from the perspective of people in conflict is paramount, especially for soldiers from peacetime armies. Civil-military engagement is a necessary competency to improve the quality of interactions between soldiers and civilians in conflict. Immersion training, such as the scenario described above, opens a niche for WPS in the modern army, to decondition combative tendencies and include the experiences of marginalised groups in military training. Professional development based on the Protection of Civilians (Table 4.2) themes will prepare soldiers for the complexity of civil-military objectives in today’s war zones.[15]

Table 4.2

NATO Model for the Protection of Civilians

Conclusion

WPS calls for political action to limit the proliferation of deadly weapons and redirect military spending to peace promotion. Increasing the professional capacity of women in destabilised countries is a shared WPS-human security goal which allows women to invest in domestic revenue streams and stay involved in the peacemaking process. Both civilian and servicewomen voice non-violent mediation strategies that mobilise whole societies towards economic growth. The integration of WPS into CAF strategic planning will foster a culture of gender-inclusive service and have lasting benefits for health and stability of the international community.

NATO forces are pivoting towards human security and conflict prevention strategies that focus on insecurities rather than threats. Development-based over instead of protection-based methods prioritise the conservation of civilian livelihood and public infrastructure rather than trying to defeat an enemy. Training exercises need to simulate the acting ground for soldiers to put the Protection of Civilians into practice and become well-versed on reconstruction techniques. The precision of force is a necessary element of peace-oriented service to prevent undue loss in the civil-military sphere.

Members of the armed forces train to defend people and go to war for their country. Learning to operate in tactical environments and rehearse battle procedure improves their ability to survive in dangerous situations. Hosting training events similar to ones led by the Peace Support Training Center Centre will incorporate WPS concepts into military forms of engagement and reduce the volatility of armed interactions. Contributions from soldiers in the CAF that are sincere and respectful of host nations and their right to self-determination will strengthen the Canadian flag a symbol of peace.

End Notes:

[1]. “S/RES/1325 (2000) Security Council,” 2000; Shannon Lewis-Simpson and Sarah Jane Meharg, Human Security and the Canadian Military: Theories, Concepts, and Future Considerations, 2023.

[2]. Lewis-Simpson and Meharg, Human Security and the Canadian Military: Theories, Concepts, and Future Considerations.

[3]. “Where Is the Peace in Canada’s Women Peace and Security Agenda?”

[4]. “Where Is the Peace in Canada’s Women Peace and Security Agenda?”

[5]. Canada. Global Affairs Canada, Gender Equality, a Foundation for Peace: Canada’s National Action Plan 2017–2022 for the Implementation of the UN Security Council Resolutions on Women, Peace and Security., 2017.

[6]. Susan A. Bartels, Carla King, and Sabine Lee, “‘When It’s a Girl, They Have a Chance to Have Sex With Them. When It’s a Boy…They Have Been Known to Rape Them’: Perceptions of United Nations Peacekeeper-Perpetrated Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Against Women/Girls Versus Men/Boys in Haiti,” Frontiers in Sociology 6 (September 24, 2021), https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.664294.

[7] Lewis-Simpson and Meharg, Human Security and the Canadian Military: Theories, Concepts, and Future Considerations.

[8]. “The Green Belt Movement,” n.d., www.greenbeltmovement.org.

[9]. Stéfanie von Hlatky, Deploying Feminism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

[10]. Canada. Global Affairs Canada, Gender Equality, a Foundation for Peace: Canada’s National Action Plan 2017–2022 for the Implementation of the UN Security Council Resolutions on Women, Peace and Security.; “Where Is the Peace in Canada’s Women Peace and Security Agenda?”

[11]. Author’s personal experience.

[12]. Lewis-Simpson and Meharg, Human Security and the Canadian Military: Theories, Concepts, and Future Considerations.

[13] Lewis-Simpson and Meharg; Rob McRae and Don Hubert, “Human Security and the New Diplomacy - Protecting People, Promoting Peace,” 2001.

[14]. Author’s personal experience.

[15]. Lewis-Simpson and Meharg, Human Security and the Canadian Military: Theories, Concepts, and Future Considerations.